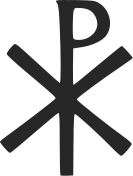

The Chi Rho is one of the earliest

christograms used by Christians. It is

formed by superimposing the first two letters in the Greek spelling of

the word

Christ (

Greek : "Χριστός" ), chi = ch and rho =

r, in such a way to produce the

monogram ☧. The Chi-Rho

symbol was also used by pagan Greek scribes to mark, in the margin, a

particularly valuable or relevant passage; the combined letters Chi and

Rho standing for chrēston, meaning "good."

Although not technically a cross, the Chi Rho invokes the

crucifixion of Jesus as well as symbolizing his status as the Christ.

There is early evidence of the Chi Rho symbol on Christian Rings of the

third century.

The labarum (Greek:

λάβαρον) was a

vexillum (military standard) that

displayed the "Chi-Rho"

symbol, formed from the first two

Greek letters of the word "Christ"

(Greek:

ΧΡΙΣΤΟΣ, or Χριστός) Chi (χ)

and Rho (ρ).

It was first used by the

Roman emperor

Constantine I. Since the vexillum

consisted of a flag suspended from the crossbar of a cross, it was

ideally suited to symbolize

crucifixion. The Chi-Rho symbol was

also used by Greek scribes to mark, in the margin, a particularly

valuable or relevant passage; the combined letters Chi and Rho standing

for chrēston, meaning "good."

Flavius Gratianus (18 April/23 May 359 25

August 383), known usually by the

anglicised name Gratian, was a

Western Roman Emperor from 375 to 383.

He favoured the Christian religion against

Roman polytheism, refusing the

traditional polytheistic attributes of the emperors and removing the

Altar of Victory from the

Roman Senate.

Life

Gratian was the son of Emperor

Valentinian I by

Marina Severa, and was born at

Sirmium (now

Sremska Mitrovica,

Serbia) in

Pannonia. He was named after his

grandfather

Gratian the Elder. Gratian was first

married to

Flavia Maxima Constantia, daughter of

Constantius II. His second wife was

Laeta. Both marriages remained

childless. His stepmother was Empress

Justina and his paternal half siblings

were Emperor

Valentinian II,

Galla and Justa.

On 4 August 367 he received from his father the

title of

Augustus. On the death of Valentinian

(17 November 375), the troops in Pannonia proclaimed his infant son (by

a second wife Justina) emperor under the title of

Valentinian II.

Gratian acquiesced in their choice; reserving for

himself the administration of the

Gallic

provinces, he handed over

Italy,

Illyricum and

Africa to Valentinian and his mother,

who fixed their residence at

Mediolanum. The division, however, was

merely nominal, and the real authority remained in the hands of Gratian.

The

Eastern Roman Empire was under the rule

of his uncle

Valens. In May, 378 Gratian completely

defeated the

Lentienses, the southernmost branch of

the

Alamanni, at the

Battle of Argentovaria, near the site

of the modern

Colmar. Later that year, Valens met his

death in the

Battle of Adrianopole on 9 August.

Valens refused to wait for Gratian and his army to arrive and assist in

defeating the host of

Goths,

Alans and

Huns; as a result, two-thirds of the

eastern Roman army were killed as well.

In the same year, the government of the Eastern

Empire devolved upon Gratian, but feeling himself unable to resist

unaided the incursions of the barbarians, he promoted

Theodosius I on 19 January 379 to

govern that portion of the empire. Gratianus and Theodosius then cleared

the

Balkans of

barbarians in the

Gothic War (376-382).

For some years Gratian governed the empire with

energy and success but gradually sank into indolence, occupying himself

chiefly with the pleasures of the chase, and became a tool in the hands

of the

Frankish general

Merobaudes and bishop

St. Ambrose of

Milan.

By taking into his personal service a body of

Alans, and appearing in public in the dress of a

Scythian warrior, after the disaster of

the Battle of Adrianopole, he aroused the contempt and resentment of his

Roman troops. A Roman general named

Magnus Maximus took advantage of this

feeling to raise the standard of revolt in

Britain and invaded

Gaul with a large army. Gratian, who

was then in

Paris, being deserted by his troops,

fled to

Lyon. There, through the treachery of

the governor, Gratian was delivered over to one of the rebel generals,

Andragathius, and assassinated on 25 August 383.

Empire

and religion

The reign of Gratian forms an important epoch in

ecclesiastical history, since during that period

Orthodox Christianity for the first

time became dominant throughout the empire.

Under the influence of Ambrosius, Gratian

prohibited

Pagan worship at

Rome; refused to wear the insignia of

the

pontifex maximus as unbefitting a

Christian; removed the

Altar of Victory from the

Senate House at Rome, despite protests

of the pagan members of the Senate, and confiscated its revenues;

forbade legacies of real property to the

Vestals; and abolished other privileges

belonging to them and to the pontiffs. Nevertheless he was still

deified after his death.

Gratian also published an edict that all their

subjects should profess the faith of the bishops of Rome and Alexandria

(i.e., the Nicene faith). The move was mainly thrust at the various

beliefs that had arisen out of

Arianism, but smaller dissident sects,

such as the

Macedonians, were also prohibited.