Valens Roman Emperor 364-378 A.D. Biography of

Early Christian Roman Emperor and Authentic Ancient Roman Coins for Sale

Own certified authentic ancient Roman coins of Valens Roman Emperor

All coins come with a certificate of authenticity and a lifetime

guarantee of authenticity.

Example of Authentic Ancient

Coin of:

Valens - Roman

Emperor: 364-378 A.D. -

Bronze AE3 Sirmium mint: 364-367A.D.

Reference: Sirmium RIC 6b

D N VALENS P F AVG, pearl diademed, draped & cuirassed bust right

RESTITVTOR REIP, emperor standing facing, head right, holding laburum &

Victory on globe, HSIRM in ex.

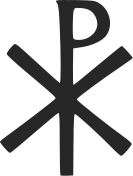

The Chi Rho is one of the earliest

christograms used by Christians. It is

formed by superimposing the first two letters in the Greek spelling of

the word

Christ (

Greek : "Χριστός" ), chi = ch and rho =

r, in such a way to produce the

monogram ☧. The Chi-Rho

symbol was also used by pagan Greek scribes to mark, in the margin, a

particularly valuable or relevant passage; the combined letters Chi and

Rho standing for chrēston, meaning "good."

Although not technically a cross, the Chi Rho invokes the crucifixion

of Jesus as well as symbolizing his status as the Christ. There is early

evidence of the Chi Rho symbol on Christian Rings of the third century.

The labarum (Greek:

λάβαρον) was a

vexillum (military standard) that

displayed the "Chi-Rho"

symbol, formed from the first two

Greek letters of the word "Christ"

(Greek:

ΧΡΙΣΤΟΣ, or Χριστός) — Chi (χ)

and Rho (ρ).

It was first used by the

Roman emperor

Constantine I. Since the vexillum

consisted of a flag suspended from the crossbar of a cross, it was

ideally suited to symbolize

crucifixion. The Chi-Rho symbol was

also used by Greek scribes to mark, in the margin, a particularly

valuable or relevant passage; the combined letters Chi and Rho standing

for chrēston, meaning "good."

Flavius Julius Valens (Latin:

FLAVIUS IVLIVS VALENS AVGVSTVS; 328 – 9 August 378) was

Roman Emperor (364-378), after he was

given the Eastern part of the empire by his brother

Valentinian I. Valens, sometimes known

as the

Last True Roman, was defeated and

killed in the

Battle of Adrianople, which marked the

beginning of the fall of the

Western Roman Empire.

Life

Appointment

to emperor

Valens and his brother

Flavius Valentinianus (Valentinian)

were both born 48 miles west of

Sirmium (modern

Sremska Mitrovica,

Serbia), in the town of Cibalae (Vinkovci,

Croatia) in 328 and 321, respectively.

They had grown up on estates purchased by their father,

Gratian the Elder, in Africa and

Britain. While Valentinian had enjoyed a successful military career

prior to his appointment as emperor, Valens apparently had not. He had

spent much of his youth on the family's estate and only joined the army

in the 360s, participating with his brother in the Persian campaign of

Emperor

Julian.

He restored some religious persecution, and was

Arian.

In February 364, reigning Emperor

Jovian, while hastening to

Constantinople to secure his claim to

the throne, was

asphyxiated during a stop at Dadastana,

100 miles east of

Ankara. Among Jovian's agents was

Valentinian, a tribunus scutariorum. He was proclaimed

Augustus on 26 February, 364.

Valentinian felt that he needed help to govern the large and troublesome

empire, and, on 28 March of the same year, appointed his brother Valens

as co-emperor in the palace of

Hebdomon. The two Augusti

travelled together through Adrianople and Naissus to

Sirmium, where they divided their

personnel, and Valentinian went on to the West.

Valens obtained the eastern half of the

Balkan Peninsula,Greece,

Egypt,

Syria and

Anatolia as far east as Persia. Valens

was back in his capital of Constantinople by December 364.

Revolt

of Procopius

Valens inherited the eastern portion of an empire

that had recently retreated from most of its holdings in

Mesopotamia and

Armenia because of a treaty that his

predecessor Jovian had made with

Shapur II of the

Sassanid Empire. Valens's first

priority after the winter of 365 was to move east in hopes of shoring up

the situation. By the autumn of 365 he had reached Cappadocian Caesarea

when he learned that a usurper had proclaimed himself in Constantinople.

When he died, Julian had left behind one surviving relative, a maternal

cousin named

Procopius. Procopius had been charged

with overseeing a northern division of Julian's army during the Persian

expedition and had not been present with the imperial elections when

Julian's successor was named. Though Jovian made accommodations to

appease this potential claimant, Procopius fell increasingly under

suspicion in the first year of Valens' reign.

After narrowly escaping arrest, he went into hiding

and reemerged at Constantinople where he was able to convince two

military units passing through the capital to proclaim him emperor on 28

September 365. Though his early reception in the city seems to have been

lukewarm, Procopius won favor quickly by using propaganda to his

advantage: he sealed off the city to outside reports and began spreading

rumors that Valentinian had died; he began minting coinage flaunting his

connections to the Constantinian dynasty; and he further exploited

dynastic claims by using the widow and daughter of

Constantius II to act as showpieces for

his regime. This program met with some success, particularly among

soldiers loyal to the Constantinians and eastern intellectuals who had

already begun to feel persecuted by the Valentinians.

Valens, meanwhile, faltered. When news arrived that

Procopius had revolted, Valens considered

abdication and perhaps even

suicide. Even after he steadied his

resolve to fight, Valens's efforts to forestall Procopius were hampered

by the fact that most of his troops had already crossed the

Cilician gates into

Syria when he learned of the revolt.

Even so, Valens sent two legions to march on Procopius, who easily

persuaded them to desert to him. Later that year, Valens himself was

nearly captured in a scramble near

Chalcedon. Troubles were exacerbated by

the refusal of Valentinian to do any more than protect his own territory

from encroachment. The failure of imperial resistance in 365 allowed

Procopius to gain control of the dioceses of

Thrace and Asiana by year's end.

Only in the spring of 366 had Valens assembled enough

troops to deal with Procopius effectively. Marching out from Ancyra

through

Pessinus, Valens proceeded into

Phrygia where he defeated Procopius's

general Gomoarius at the

Battle of Thyatira. He then met

Procopius himself at Nacoleia and convinced his troops to desert him.

Procopius was executed on 27 May and his head sent to Valentinian in

Trier for inspection.

War

against the Goths

The

Gothic people in the northern region

had supported Procopius in his revolt against Valens, and Valens had

learned the Goths were planning an uprising of their own. These Goths,

more specifically the Tervingi, were at the time under the leadership of

Athanaric and had apparently remained

peaceful since their defeat under Constantine in 332. In the spring of

367, Valens crossed the Danube and marched on Athanaric's Goths. These

fled into the

Carpathian Mountains, and eluded

Valens' advance, forcing him to return later that summer. The following

spring, a Danube flood prevented Valens from crossing; instead the

emperor occupied his troops with the construction of fortifications. In

369, Valens crossed again, from

Noviodunum, and attacked the

north-easterly Gothic tribe of Greuthungi before facing Athanaric's

Tervingi and defeating them. Athanaric pled for treaty terms and Valens

gladly obliged. The treaty seems to have largely cut off relations

between Goths and Romans, including

free trade and the exchange of troops

for tribute. Valens would feel this loss of military manpower in the

following years.

Conflict

with the Sassanids

Among Valens' reasons for contracting a hasty and not

entirely favorable peace in 369 was the deteriorating state of affairs

in the East. Jovian had surrendered Rome's much disputed claim to

control over Armenia in 363, and

Shapur II was eager to make good on

this new opportunity. The

Sassanid ruler began enticing Armenian

lords over to his camp and eventually forced the defection of the

Arsacid Armenian king,

Arsakes II, whom he quickly arrested

and incarcerated. Shapur then sent an invasion force to seize

Caucasian Iberia and a second to

besiege Arsaces' son,

Pap, in the fortress of Artogerassa,

probably in 367. By the following spring, Pap had engineered his escape

from the fortress and flight to Valens, whom he seems to have met at

Marcianople while campaigning against the Goths.

Already in the summer following his Gothic

settlement, Valens sent his general Arinthaeus to re-impose Pap on the

Armenian throne. This provoked Shapur himself to invade and lay waste to

Armenia. Pap, however, once again escaped and was restored a second time

under escort of a much larger force in 370. The following spring, larger

forces were sent under Terentius to regain Iberia and to garrison

Armenia near Mount Npat. When Shapur counterattacked into Armenia in

371, his forces were bested by Valens' generals Traianus and Vadomarius

at Bagavan. Valens had overstepped the 363 treaty and then successfully

defended his transgression. A truce settled after the 371 victory held

as a quasi-peace for the next five years while Shapur was forced to deal

with a

Kushan invasion on his eastern

frontier.

Meanwhile, troubles broke out with the boy-king Pap,

who began acting in high-handed fashion, even executing the Armenian

bishop

Narses and demanding control of a

number of Roman cities, including

Edessa. Pressed by his generals and

fearing that Pap would defect to the Persians, Valens made an

unsuccessful attempt to capture the prince and later had him executed

inside Armenia. In his stead, Valens imposed another Arsacid,

Varazdat, who ruled under the regency

of the

sparapet Musel

Mamikonean, a friend of Rome.

None of this sat well with the Persians, who began

agitating again for compliance with the 363 treaty. As the eastern

frontier heated up in 375, Valens began preparations for a major

expedition. Meanwhile, trouble was brewing elsewhere. In

Isauria, the mountainous region of

western

Cilicia, a major revolt had broken out

in 375 which diverted troops formerly stationed in the east.

Furthermore, by 377, the

Saracens under

Queen Mavia had broken into revolt and

devastated a swath of territory stretching from

Phoenicia and

Palestine as far as the

Sinai. Though Valens successfully

brought both uprisings under control, the opportunities for action on

the eastern frontier were limited by these skirmishes closer to home.

In 375, Valens' older brother Valentinian, while in

Pannonia had suffered a burst

blood vessel in his skull, which

resulted in his death on 17 November, 375.

Gratian, Valentinian's son and Valens'

nephew, had already been associated with his father in the imperial

dignity and was joined by his half-brother

Valentinian II who was elevated, on

their father's death, to

Augustus by the imperial troops in

Pannonia.

Gothic

War

Valens' plans for an eastern campaign were never

realized. A transfer of troops to the western empire in 374 had left

gaps in Valens' mobile forces. In preparation for an eastern war, Valens

initiated an ambitious recruitment program designed to fill those gaps.

It was thus not unwelcome news when Valens learned that the Gothic

tribes had been displaced from their homeland by an invasion of

Huns in 375 and were seeking asylum

from him. In 376, the

Visigoths advanced to the far shores of

the lower Danube and sent an ambassador to Valens who had set up his

capitol in

Antioch. The Goths requested shelter

and land in the

Balkan peninsula. An estimated 200,000

Gothic Warriors and altogether 1,000,000 Gothic persons were along the

Danube in

Moesia and the ancient land of

Dacia.

As Valens' advisers were quick to point out, these

Goths could supply troops who would at once swell Valens' ranks and

decrease his dependence on provincial troop levies — thereby increasing

revenues from the recruitment tax. Among the Goths seeking asylum was a

group led by the chieftain

Fritigern. Fritigern had enjoyed

contact with Valens in the 370s when Valens supported him in a struggle

against Athanaric stemming from Athanaric's persecution of Gothic

Christians. Though a number of Gothic

groups apparently requested entry, Valens granted admission only to

Fritigern and his followers. This did not, however, prevent others from

following.

When Fritigern and his Goths undertook the crossing,

Valens's mobile forces were tied down in the east, on the Persian

frontier and in Isauria. This meant that only

riparian units were present to

oversee the Goths' settlement. The small number of imperial troops

present prevented the Romans from stopping a Danube crossing by a group

of Goths and later by Huns and

Alans. What started out as a controlled

resettlement mushroomed into a massive influx. And the situation grew

worse. When the riparian commanders began abusing the Visigoths under

their charge, they revolted in early 377 and defeated the Roman units in

Thrace outside of Marcianople.

After joining forces with the Ostrogoths and

eventually the Huns and Alans, the combined barbarian group marched

widely before facing an advance force of imperial soldiers sent from

both east and west. In a

battle at Ad

Salices, the Goths were once again victorious, winning

free run of Thrace south of the

Haemus. By 378, Valens himself was able

to march west from his eastern base in Antioch. He withdrew all but a

skeletal force — some of them Goths — from the east and moved west,

reaching Constantinople by 30 May, 378. Meanwhile, Valens' councilors,

Comes

Richomeres, and his generals Frigerid,

Sebastian, and Victor cautioned Valens and tried to persuade him to wait

for Gratian's arrival with his victorious legionaries from Gaul,

something that Gratian himself strenuously advocated. What happened next

is an example of

hubris, the impact of which was to be

felt for years to come. Valens, jealous of his nephew Gratian's success,

decided he wanted this victory for himself.

Battle

of Adrianople and death of Valens

After a brief stay aimed at building his troop

strength and gaining a toehold in Thrace, Valens moved out to

Adrianople. From there, he marched

against the confederated barbarian army on 9 August 378 in what would

become known as the

Battle of Adrianople. Although

negotiations were attempted, these broke down when a Roman unit sallied

forth and carried both sides into battle. The Romans held their own

early on but were crushed by the surprise arrival of Visigoth cavalry

which split their ranks.

The primary source for the battle is

Ammianus Marcellinus. Valens had left a

sizeable guard with his baggage and treasures depleting his force. His

right wing, cavalry, arrived at the Gothic camp sometime before the left

wing arrived. It was a very hot day and the Roman cavalry was engaged

without strategic support, wasting its efforts while they suffered in

the heat.

Meanwhile Fritigern once again sent an emissary of

peace in his continued manipulation of the situation. The resultant

delay meant that the Romans present on the field began to succumb to the

heat. The army's resources were further diminished when an ill timed

attack by the Roman archers made it necessary to recall Valens'

emissary, Comes Richomeres. The archers were beaten and retreated in

humiliation.

Gothic cavalry under the command of Althaeus and

Saphrax then struck and, with what was probably the most decisive event

of the battle, the Roman cavalry fled. From here, Ammianus gives two

accounts of Valen's demise. In the first account, Ammianus states that

Valens was "mortally wounded by an arrow, and presently breathed his

last breath," (XXXI.12) His body was never found or given a proper

burial. In the second account, Ammianus states the Roman infantry was

abandoned, surrounded and cut to pieces. Valens was wounded and carried

to a small wooden hut. The hut was surrounded by the Goths who put it to

the torch, evidently unaware of the prize within. According to Ammianus,

this is how Valens perished (XXXI.13.14-6).

The church historian

Socrates likewise gives two accounts

for the death of Valens.

Some have asserted that he was burnt to death in

a village whither he had retired, which the barbarians assaulted and

set on fire. But others affirm that having put off his imperial robe

he ran into the midst of the main body of infantry; and that when

the cavalry revolted and refused to engage, the infantry were

surrounded by the barbarians, and completely destroyed in a body.

Among these it is said the emperor fell, but could not be

distinguished, in consequence of his not having on his imperial

habit.

When the battle was over, two-thirds of the eastern

army lay dead. Many of their best officers had also perished. What was

left of the army of Valens was led from the field under the cover of

night by Comes Richomer and General Victor.

J.B. Bury, a noted historian of the

period, provides specific interpretation on the significance the battle:

it was "a disaster and disgrace that need not have occurred."

For Rome, the battle incapacitated the government.

Emperor Gratian, nineteen years old, was overcome by the debacle, and

until he appointed

Theodosius I, unable to deal with the

catastrophe which spread out of control.

Legacy

Adrianople was the most significant event in Valens'

career. The battle of Adrianople was significant for yet another reason:

the evolution of warfare. Until that time, the Roman infantry was

considered invincible, and the evidence for this was considerable.

However, the Gothic cavalry completely changed all that. Although J.B.

Bury states that records are incomplete for the 5th century, all during

the 4th and 6th centuries, history shows that the cavalry took over as

the principal Roman weapon of war on land.

"Valens was utterly undistinguished, still only a

protector, and possessed no military ability: he betrayed his

consciousness of inferiority by his nervous suspicion of plots and

savage punishment of alleged traitors," writes

A.H.M. Jones. But Jones admits that "he

was a conscientious administrator, careful of the interests of the

humble. Like his brother, he was an ernest Christian." To have died in

so inglorious a battle has thus come to be regarded as the nadir of an

unfortunate career. This is especially true because of the profound

consequences of Valens' defeat. Adrianople spelled the beginning of the

end for Roman territorial integrity in the late empire and this fact was

recognized even by contemporaries. Ammianus understood that it was the

worst defeat in Roman history since the

Battle of Cannae (31.13.19), and

Rufinus called it "the beginning of

evils for the Roman empire then and thereafter."

Valens is also credited with the commission of a

short history of the Roman State. This work, produced by Valens'

secretary

Eutropius, and known with the name

Breviarium ab Urbe condita, tells the story of Rome from its

founding. According to some historians, Valens was motivated by the

necessity of learning Roman history, that he, the royal family and their

appointees might better mix with the Roman Senatorial class.

Struggles

with the religious nature of the empire

During his reign, Valens had to confront the

theological diversity that was beginning to create division in the

Empire.

Julian (361–363), had tried to revive

the pagan religions. His reactionary attempt took advantage of the

dissensions between the different factions among the

Christians and a largely Pagan

rank and file military. However, in

spite of broad support, his actions were often viewed as excessive, and

before he died in a campaign against the Persians, he was often treated

with disdain. His death was considered a sign from

God.

Like the brothers

Constantius II and

Constans, Valens and Valentinian I held

divergent theological views. Valens was an

Arian and

Valentinian I upheld the

Nicene Creed. When Valens died however,

the cause of Arianism in the Roman East was to come to an end. His

successor

Theodosius I would endorse the Nicene

Creed.

|